Score one for the skeptics. In our previous posts we’ve used aptitude testing as a proxy for performance and the gold standard of what West Point recruiting efforts ought to be focused on. As it turns out, military scores matter more for “succeeding” in today’s Army. But is that a good thing?

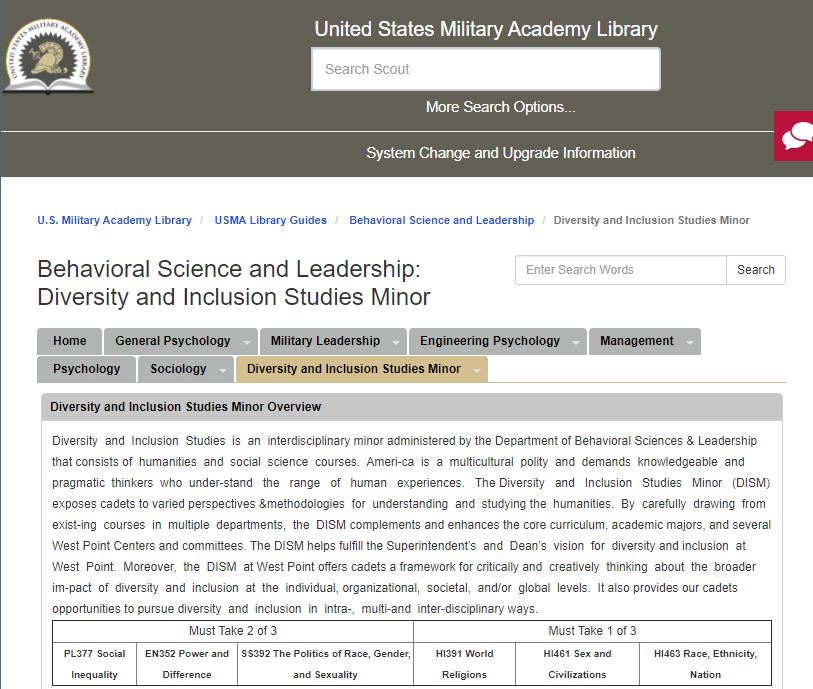

Our opinion is that finding and maintaining talent in the Service is requisite for whole-military success against increasingly dangerous foes and that neglecting our human capital is a fatal strategic mistake. Therefore, USMA ought to be screening for and accepting as many high-aptitude individuals as it can, which we have shown it is clearly not doing in favor of other considerations such as diversity and sports.

However, other commenters aren’t convinced. They haven’t hesitated to point out that West Point uses the “whole candidate score” and concept in its recruiting efforts, often noting that “it takes more than book-smarts to succeed in the Army,” and saying that we should be looking testing in light of whether it really drives or predicts performance in the Army.

As it turns out, they’re right. But perhaps they won’t like the consequences as much as the feelings they get from demoting testing’s utility.

Predicting Promotions in the Army

An academic paper recently came to our attention, authored by Col Everett Spain, who–although we did not attend his classes at the Academy– has a very positive reputation and in our passing interactions with him found him to be pleasant, thoughtful, and erudite. The abstract of the paper (not linked in entirety due to copyright) is:

The importance of leadership to organizational performance puts a premium on identifying future leaders. Early prediction of high-potential talent enables organizations to marshal scarce developmental resources and opportunities to those who are best positioned to show distinction in elevated roles. Much of the existing literature indicates that general mental ability remains the strongest predictor of future professional performance. Using data from 13 classes of West Point graduates who stayed in the Army to be considered for at least early promotion to the rank of major (N = 5,505), regression analyses indicate that cadet military grade point average surpasses both cognitive ability and academic performance by a considerable margin in the ability to predict future professional outcomes such as selection for early promotion or battalion command. Moreover, these differences in predicting managerial career outcomes endure over 16 years. Both practical and theoretical implications are discussed.

Everett S. Spain, Eric Lin & Lissa V. Young (2020) Early predictors of successful military careers among West Point cadets, Military Psychology, 32:6, 389-407, DOI: 10.1080/08995605.2020.1801285

This is a very interesting study, and I recommend purchasing / reading the entire thing. It seems methodologically sound in its controls and calculations. Spain tested whether “the probability that a West Pointer’s career outcome was predicted by models incorporating cognitive ability.” For “Career outcomes”, it selects early promotion to Major, Lieutenant Colonel, and selection to Battalion Command as measurable events. For cognitive ability, (the “g” factor) it uses SATs as a proxy. It finds (among other things) that:

- The Army promotion process actively selects against intelligence in its promotion events. “cognitive ability was a negative predictor of officer career success in both the short term and longer term… a 100-point increase in a cadet’s SAT score (which is approximately one standard-deviation) was associated with an 8% decrease in odds of being promoted early to major… controlling for number of years deployed increased this negative effect of measured cognitive ability by four percentage points, with each positive unit change in SATTOT associated with 12% smaller odds of early promotion… SATTOT also negatively predicted EPL and BC deeper in an officer’s career.”

If you’re not familiar with the Army careers, promotions to Major are where the post-mandatory-obligation cohort gets its first indication of who will have a “successful” career. They see who gets promoted early ( “Below the Zone (BZ)), who will just do ok, and who needs to start looking at getting out.

So now that we see that intelligence is inversely related to promotions, we have to wonder what is positively related?

Academic GPA and Career Success

- The paper points out that regarding Academic GPA (AGPA), “suggesting a 1-point increase in AGPA is associated with a 63% increased odds of being selected for EPM.”

Parenthetically, we are curious about how to devise an academic system in which academic performance is inversely related to cognitive ability–here posited by the situation in which higher test scores (inversely predictive of Army career success) do not lead to a higher AGPA (very predictive of Army career success). Indeed, we found in our earlier posts that test scores were indeed significantly and positively correlated with GPAs. But perhaps all the Additional Instruction sessions and STAP make up the difference. Anyway, apparently West Point has done it, perhaps with more classes on Race Theory and Social Inequality:

Military GPA Is More Important Than Aptitude

The paper finds that Military GPAs are most predictive of career success. The Military GPA:

captured each cadet’s cumulative job evaluations ratings and military course grades over 4 years and reflected the cadets’ overall performance in meeting military training requirements (Lewis et al., 2005). The majority (70%) of this score was the force-distributed evaluation of the cadets’ job performances in each of their assigned followership or leadership roles. During their 11 terms, only 20% of cadets in any were allowed to receive an “A” rating, 40% of cadets were allowed to receive a “B,” and the remaining 40% earned a “C” or below during each grading event (Milan, Bourne, Zazanis, & Bartone, 2002). After each of the terms, cadets received a military development grade calculated by the following formula: 50% was assigned by their cadet company tactical officer (typically a US Army captain with legal command authority over a subgroup of 125 cadets), 30% was assigned by their immediate cadet boss, and 20% was assigned by their second- and third-level cadet bosses (Milan et al., 2002). Since cadets were typically in formal supervisory positions at all times apart from their first year at the Academy, “tactical officers and cadet supervisors are instructed to consider 12 behavioral domains in relation to the cadet’s leader performance” (Bartone et al., 2009, p. 503). These include duty motivation, military bearing, planning and organizing, decision making, oral and written communication, delegating, supervising, developing subordinates, teamwork, influencing others, consideration for others, and professional ethics (U.S. Corps of Cadets, 1995), all of which were either direct or indirect expectations of Army officers (U.S. Army, 2019).”

The military GPA turns out to be most predictive of promotions in the Army:

Of the 12 behavioral domains measured by the MGPA, at least 3 (planning & organizing, decision-making, communication) are heavily g-loaded. The rest are behavioral. This shows that personality traits, or as Spain points out (excluding “technical skills,” which are definitely cognitive characteristics):

noncognitive characteristics drive MGPA and which of these are most predictive of future officer career outcomes. A few of the possibilities including conscientiousness, commitment, followership, charisma, technical skills, agreeableness, relationship strength, demographic similarity, etc.

are driving promotions in the Army. So we see that that personality conformance as rated by superiors (“commitment, followership, agreeableness”) through the OER process is taking precedence over ability. In other words, this is empirical validation of John Reed’s assertion that sucking up matters most.

This goes a long way to explaining why we’re still in Afghanistan. It’s adverse selection in action. Nobody can figure out how to leave, and even if they could, no one would tell their boss he’s wrong.

- The paper provides helpful statistics of the groups of military that get out of the service, those that stay in, and those that achieve “success events”.

It’s interesting to watch the mean AGPAs and SATTOTs decline and MGPAs increase as the cohorts move further “up” the career ladder.

Conclusion

So, all right, all right, you doubting Thomases- you are correct. Test Scores aren’t all that when it comes to Army promotions.

Meanwhile, our officer corps is indeed getting stupider. We find this confirmed in other contemporary literature on “Office Quality in the All-Volunteer Force” (h/t Anatoly Karlin at Unz):

In this paper, we show that the intelligence of officers in the Marines, as measured by scores on the General Classification Test (GCT), a test that all officers take, has steadily and significantly declined since 1980 [through 2014 in the paper – UD]… This negative trend could contribute to adverse consequences for military effectiveness and national security.

Matthew F. Cancian, Michael W. Klein (2015) Military Officer Quality in the All-Volunteer Force, National Bureau of Economic Research, Wroking Paper 21372, http://www.nber.org/papers/w21372

Not a big deal, as long as the people getting promoted have the right non-cognitive abilities to get promoted, right? After all, the DOD is doing its best to ensure that aptitude tests “do not adversely impact diversity.” We can’t wait to see these studies replicated with USMA classes from 2012-2020.

This has several implications.

First, if g is actually negatively correlated to “success in the Army”, and g is positively correlated to every positive major life outcome (see Spain’s sources as well as just about every other work on mental ability, and sociological studies like The Bell Curve, then “success in the army” can inferred to be a negative life outcome. We can expect an Idiocracy-like filtering of talent at our highest ranks. And in fact, from Spain’s statistics above, this is exactly what is happening.

The paper doesn’t speak to whether Aptitude scores ought to predict better performance in the Army. It talks about whether aptitude scores do predict performance in the Army. This is an important distinction. For any organization to actively select against mental ability in its leadership is a bold strategy, and we see that the Army–charged with fighting and winning our nation’s wars– does indeed do that.

In sum, this reinforces our earlier point of view that “success in the army” is more a function of personality conformance and not selecting the “best and brightest.”

And it is now proven that the Army selects against intelligence at higher ranks. This behavior only makes sense if one believes that mental ability (“g“) doesn’t matter at all to anticipating and defeating future adversaries. And recovering from this is very hard, because it will take a culture change as well as undoing the negative signaling already in place.

Second, if Promotions, and not Ability or Winning Wars, equals Success in the Army, we have some recommendations for West Point:

- For admissions, since g measures are negatively correlated to success in the Army, West Point should select bare minimum of aptitude and maximize on personality tests weighting selecting for the non-g loaded measures of MGPA. Scrap the SATs and ACTs, and go straight to the personality inventory.

- If the Academy wants to produce more “successful” officers, this means it should flip its entire grading scheme to reflect importance of MGPA. Weight military grades at 65% instead of Academics for CQPAs.

We’ve shown that West Point’s admissions policies have been more about supporting promotions for its managers rather than developing the best possible officer corps. These are merely suggestions to go all the way.

Of course, West Point could skip all of the complicated grading and just go by the time-tested measure of a soldier, the face. Physiognomy doesn’t lie.

As always, factual corrections and thoughtful criticism are welcome.

Facial appearance: MacArthur once said of John Wayne “He looks more like a soldier than any soldier I know” yet Wayne famously avoided military service. Jimmy Stewart, the boy next door, was only one of six soldiers to rise from private to colonel during WWII.

These studies, though interesting, fail to account for “being in the right place at the right time”. I knew several officers whose careers were “tied to rockets” that got derailed due to one unfortunate incident.

Hard to see how IQ would be negatively correlated with “being in the right place at the right time”.

The studies don’t purport to identify every factor that goes into promotion.

Stewart’s transition from private to officer pilot was of course by application, not really by promotion.

This is supported by my experience in the Canadian Forces as well

Who are you and do you need help?

They don’t want any high-ranks clever enough to organize and pull off a coup. Eisenhower was the last top brass in the White House.

Hard to get to be a popular commander if you’re not fighting a popular war.